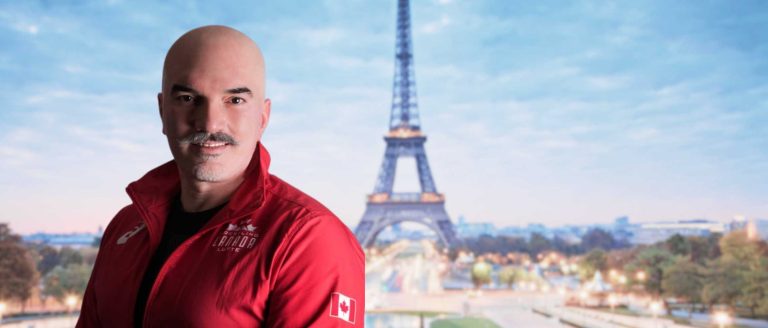

JOSHUA GILES

Affiliate Assistant Professor

Division:

Research

Site:

Vancouver Island – University of Victoria

Renowned for his contributions to orthopaedic biomechanics, Dr. Joshua Giles specializes in enhancing functional outcomes in shoulder arthroplasty. In an illuminating spotlight, Dr. Giles delves into his aspirations for positively impacting patients’ lives and underscores the necessity of realistic expectations for those considering a career in academia. Outside the research realm, he dedicates time to mentoring students and finds solace in exploring Victoria’s natural beauty through hiking and engaging in home improvement projects.

Can you share a little bit about your educational background and journey, and how you got to where you are today?

I completed a BESc in Mechanical Engineering at the University of Western Ontario in 2009. Coming from a small town, I had not been exposed to engineering and high tech jobs and so really had no idea what type of work was available or what I wanted to do but by early in my second year I realized that I did not want an ‘ordinary’ engineering job and luckily later that year I had the fortune of being taught by a biomechanics professor that really opened my eyes to how mechanical engineering could be applied to the human body and to treating orthopaedic conditions. From then on I was focused on orthopaedic biomechanics through part time work and summer positions.

I then undertook my Master’s, which I transitioned to a PhD from 2009-2014 in Biomedical Engineering at the University of Western Ontario in the world-renowned Hand and Upper Limb Centre Bioengineering lab. My PhD focused on in-vitro experimental orthopaedic biomechanics, particularly how we could use that method to answer clinical questions related to shoulder sports injury treatments (e.g. bankart repairs, bony stabilization, etc.), and later studying the effects of design variations in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty, the use of which was exploding at that time.

After completing a PhD very much focused on answering clinically driven hypothesis based questions, I really wanted to learn how to develop new devices, systems, and tools to be used in orthopaedic surgery, so I took on a post-doctoral position at Imperial College London, in London, UK. I spent 3.5 years (2014-2017) living and working in central London and it was the most exciting and fun time of my life to date. My work focused on developing a surgical technical and set of engineered tools that would enable a new anatomical shoulder arthroplasty implant (being designed by my colleagues) to be implanted through a minimally invasive approach. The thought process here was that if we could make anatomical arthroplasty less invasive, we could improve outcomes, and make anatomical arthroplasty a more attractive procedure as reverse total shoulder replacement by that point had become the dominant procedure despite its own shortcomings.

In the summer of 2017, I was fortunate enough to be selected for an academic position in Mechanical Engineering at the University of Victoria and started my position in November 2017. Since starting this position and founding my lab (the Orthopaedic Technologies and Biomechanics Lab) I have worked on building a research group that both answers clinical questions (like I did in my PhD) but also always keeps in mind how that knowledge can be practically translated into the clinical setting beyond just journal articles and hence the reason to have put ‘Technologies’ prominently in the name of the group as I think doing orthopaedic biomechanical research without a clear line on how to get it into the clinic is not optimal. We conduct research in many orthopaedic and broader MSK areas but still have a strong focus on the shoulder. We use and have developed computational methods to study biomechanics and hopefully directly assist surgeons in pre-operative planning. We also use experimental methods to answer questions and validate our computational methods. And of course, we develop new technologies for the assessment and treatment of patients.

What inspired you to work in orthopaedics, specifically in orthopaedic research?

I often get this question, and unfortunately, I cannot say that I have an interesting origin story about an MSk injury I or a family member suffered that lead me to MSk biomechanics. It really was serendipity that I was taught by my eventual PhD supervisor in the first term of the second year of my undergraduate degree and that he regularly brought biomechanical examples into a course that wasn’t about biomechanics. As I said above, this really caught my attention because as an engineer in training, I obviously wanted to help people and do good in society and being able to study biomechanics and improve orthopaedic treatment by using engineering fundamentals seemed like a topic where I could have a real positive impact. As well, I just generally found it fascinating. It is for this reason that I try to do the same as my professor did and inform students about orthopaedic biomechanics early in their degrees to show them how they can have an impact.

What impact would you like to see your work have on patients, communities and society at large?

I am hopeful that my work can impact patients by improving their outcomes, most specifically their functional outcomes. One of the reasons I have stuck with shoulder research thus far in my career is that shoulder outcomes continue to be less optimal than in other orthopaedic treatments like hip and knee replacement and so there are lots of opportunities to impact patients’ lives by making engineering discoveries and innovations that can improve outcomes. I specifically said functional outcomes because quite often in arthroplasty, outcomes focus on survivorship (i.e. how long will the implant work before needing to be replaced) but in shoulder arthroplasty (specifically reverse shoulder arthroplasty) patient functional outcomes are poorer from day one than in other joints and never reach the same quality. Thus focusing on how we can not just make the implants ‘work’ for more years but also how we can make them work better from day one is a big focus of my work. We are trying to address this question by developing tools that surgeons can use to improve their consideration of patient specific factors that can influence the optimal way they should implant the arthroplasty components.

What excites you most about your work? What are you most proud of?

There are three things that most excite me about my work: 1) the way that the work I and my students do can have a tangible impact on making peoples’ lives better for longer, 2) the opportunity to work with young, excited students and help them find a path and career that they will enjoy like I enjoy mine, 3) the fact that every day is different and that I can follow the aspects of orthopaedic research that interest me.

What is one piece of advice that you’d like to give to current trainees?

Unfortunately, the advice I would give is not necessarily a hopeful thing. I would say and often do say to trainees that are considering whether to do a PhD and, more specifically those interested in becoming an academic, that they need to come in with their eyes open to the fact that PhDs are very challenging and despite putting in tons of work, academic jobs are very few. Thus if that is their path, they need to 1) understand that despite all their efforts they may not get an academic job and know what their plan is if that happens, 2) if you want that type of job, you need to do everything you can during your training to make sure you are going to be a strong candidate and there is more to it than just doing good research.

When you’re not working, where can we find you?

When I am not working you would find me either doing projects around my house or hiking in and around Victoria.